My first encounter with the works of Francis Bacon came in 2011 at the Centre Pompidou in Paris. I spent the better part of a week gaping at works of the early modernists and gee-whizzing around the Museum’s enormous collection of ultra-famous paintings from the early 20th century. I cannot remember every detail of my visit, but I do recall feeling bewildered each afternoon when I’d reach the gallery where Bacon’s triptych, Three Figures in a Room was on display. These images made me feel profoundly uncomfortable, and after a few uneasy moments in front of the canvases I would usually decide that I’d had enough modern art for the day and double back through the museum, taking one last look at the pieces by Picasso, Matisse, and Duchamp before heading off to the bar to sketch and read.

I hadn’t thought much about Francis Bacon in the intervening years, and It was only by coincidence that I recently came across Michael Peppiatt’s extraordinary biography of the artist, Francis Bacon, Anatomy of an Enigma at Saint George’s bookstore in Berlin. Since then, I’ve found myself developing a bit of a fascination with the English painter. After a month long binge on Bacon-related documentaries, lectures, and videos, I felt the need to quickly commit some observations to paper. My aim is not to develop a thesis or to advance any particular agenda, but simply to capture some ideas about Bacon and his approach to painting that I find to be especially interesting. In addition to Peppiatt’s biography, I’ll make reference to two interviews with Bacon. The first is a 1966 interview conducted by the art critic David Sylvester, and the second is an episode of the South Bank show from 1985. This text is incomplete, and will continue to evolve as I read and think more about Bacon.

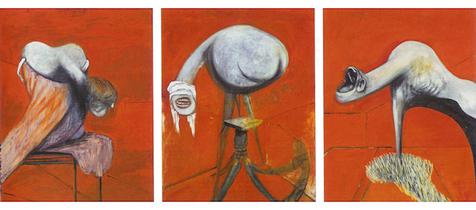

Bacon’s first great work was the 1944 triptych, Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion.⇥ The work depicts three grotesque biomorphs set against a vivid orange background. While the bodies of the figures are left indistinct and cursorily painted, the ears, lips, and teeth are rendered with an unsettling amount of detail. The figures writhe and contort atop weird pedestals, stretching their eel-like necks across the panels. The rightmost creature holds its jaw open in a frightening howl while the center figure bares its teeth at the viewer. Following a 1945 showing at the Lefevre gallery in London the art critic John Russell wrote, “They caused a total consternation. We had no name for them, and no name for what we felt about them. They were regarded as freaks, monsters irrelevant to the concerns of the day, and the product of an imagination so eccentric as not to count in any possible permanent way. They were specters at what we all hoped was going to be a feast, and most people hoped they would just quietly be put away.” Robert Mortimer found the figures to be, “Gloomily phallic (Bosch without the humour).”⇥

Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, Francis Bacon, 1944.

Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, Francis Bacon, 1944.Oil and Pastel on Board

In many ways, Three Studies set the the agenda for Bacon’s entire career. In particular, it demonstrated his remarkable ability to shock and disturb the viewer through a brutal treatment of the living figure. Scholars like Patricia Failing have pointed out that Bacon was likely influenced in this respect by George Bataille and his dissident brand of Surrealism which emphasized the base, savage, and primal aspects of life.⇥ Under Bataille’s direction, the French surrealist magazine Documents published shocking photos of screaming mouths, toes, primitive art, offal, and slaughterhouses alongside elevated academic writings from 1929 to 1930.⇥ Bataille’s edgy strand of surrealism sought to challenge our denial of the body as meat, uncomfortably drawing attention to the unpretentious and primal aspects of the human experience. Both Bataille and Bacon capitalized on the human tendency to recoil at the sight of wounds, disfigurements, bodily effluences, and other reminders of our physical frailty. Failing points out that Bacon’s work is unsettling because he depicts the body as disfigured and porous, on the verge of dissolution and decay. Bacon never paints the body as a sturdy, sealed vessel (Ingres, Rafael, Rubens). Instead, he dissolves the flesh and uncomfortably reminds the viewer of their inevitable physical decline.⇥

Bacon was preoccupied with painting the mouth in his early career, claiming that this interest could be traced to a book that he purchased in Paris, Atlas-Manuel des maladies de la bouche. The book contained hand-illustrated drawings of oral diseases which Bacon found to be very beautiful w/r/t their treatment of color. He said, “I love the mouth because it’s rather like a Turner. It’s got all these beautiful colors about it, these lovely vibrations of color between the tongue, the lips, and the teeth.” He famously said, “I always thought that I would be able to make the mouth with all the beauty of a Monet landscape, but I never did succeed in doing so.” Aside from the psychological aspects of Bacon's preoccupation with the mouth, it seems very likely that the subject simply appealed to him on a strictly visual level.⇥ Many artists have been taken with the subject of flesh and meat (Rembrandt, Soutine, Bacon), and I would suggest that this appeal is largely due to the interesting mixture of textures and colors present (same goes for wounds and orifices like the mouth). The painter of meat must convincingly portray the hard knobby texture of solid bone against the wet, slippery, and reflective surface of red flesh and milky fat. For someone intensely interested in the representation of visual phenomena in oil paint, meat presents an exciting technical challenge.

Slaughtered Ox Rembrandt. Oil |

.jpg!Blog.jpg) Carcass of Beef

Carcass of BeefChaim Soutine, 1926. Oil |

Figure with Meat Francis Bacon, 1954. Oil and Pastel on Board |

It’s worth noting that oil paint is particularly well suited to the depiction of meat. The surface qualities of masterly applied oil paint can brilliantly capture the sensation of flesh. Rembrandt’s Slaughtered Ox is rendered with loose, thick strokes of the brush in a technique which anticipates the Post-Impressionists.⇥ The brush strokes in the Slaughtered Ox are eminently visible, and Rembrandt made no attempts to soften, blend, or hide the presence of his brushwork. The paint is the image, and it’s given a texture and suppleness which brilliantly conveys the sensation of the flesh it is meant to depict. This technique is particularly appealing to a 20th century painter like Bacon because it emphasizes the special characteristics of the painted image in a time when photography could so effortlessly perform the job of illustration.⇥ For Bacon, the special (physical) properties of oil paint meant that it could convey the sensation of an object in a much more immediate fashion than photography could ever hope to. Bacon wrote very beautifully about this relationship between technique and image in a short piece about the painter Matthew Smith, “He seems to be to be one of the very few English painters since Constable and Turner to be concerned with painting, that is, with attempting to make image and technique inseparable. Painting in this sense tends towards a complete interlocking of image and paint, so that the image is the paint and vice versa. Here, the brush-stroke creates the form and does not merely fill it in. Consequently, every movement of the brush on the canvas alters the shapes and implications of the image.” [Italics are mine]

Bacon had an affinity for old masters who excelled at the physical application of oil paint. For example, Bacon had a great love for Velázquez, whose incredible brilliance lay in his ability to suggest wholly convincing forms with a shocking economy of brush strokes. Perhaps more than any other painter, Velázquez had an instinctive, physical understanding for the behavior of oil paint. As a point of comparison, Caravaggio’s incredible talents lie in his use of composition, staging, and lighting, not necessarily in his painting technique. Put another way, most of the images produced by Caravaggio would be no less breathtaking if they were photographs instead of oil paintings. Bacon’s great influences (Velázquez, Picasso, Rembrandt, Van Gogh) all created images which make sense only as oil paintings. Like these artists, Bacon developed a great command over the medium, demonstrating an ability to depict complex forms through a thoughtful application of technique. Because of the somewhat “crude” draughtsmanship on display in Bacon’s work, it’s easy to overlook his extraordinary painting technique. In Francis Bacon, The Human Body, David Sylvester points out that Bacon was just as capable of employing the delicate and economic technique of grisaille as he was at deploying viscous strikes of colorful impasto against the canvas.

When Three Studies was exhibited in 1945, Abstract Expressionism was on the ascent, and figurative art would continue to fall from favour as the attentions of the art world shifted from Paris to New York. Bacon seems to have had little interest in the zeitgeist, and was openly dismissive of Abstract Expressionism. He described Pollock’s paintings as, “Bits of old lace”, and Rothko’s color field paintings as, “The most dreary paintings that have ever been made.” In contrast to his abstract contemporaries, Bacon remained preoccupied with depicting the human figure, and was insistent on furthering the tradition of figurative art by directly referencing masters like Velázquez, Van Gogh, Degas, and Rembrandt.⇥

- Francis Bacon⇥

In large part, I think that Bacon’s art can be thought of as a proposition for the future of figurative painting. It’s a proposition which addresses two great problems facing modern painting: photography and abstraction. Photography renders the role of painting as facsimile void, and abstraction threatens to make painting vapid. Bacon’s great achievement was to show how the physicality and immediacy of oil paint can be used to deliver a wholly unique and powerful experience while still depicting the human figure. It’s important to note that Bacon did not achieve this feat by ignoring photography. In fact, his studio practice was largely based on the use of photographs for models and inspiration.⇥ Bacon almost never worked from a live model, preferring instead to paint from photographs. He drew from a wide range of images, referencing the work of Muybridge , Bataille’s Documents, the art periodical Cahier's d'Art, stills from the cinema, magazine clippings, medical textbooks, and photographic reproductions of classic works of art. In a very modern way, Bacon assimilated all of these disparate visual influences into a strange and vibrant body of painted images. Much like Gerhard Richter, Bacon was able to reinterpret the photographic image with a heightened sense of emotion and gravity. Bacon spoke eloquently about this interplay between photography and painting in a 1963 interview with Peppiatt,

- Francis Bacon [p. 239]

Bacon was a gregarious raconteur, prodigious drinker, and lived what could only be described as an excessive lifestyle. His drinking binges, sexual escapades, and gambling habits are the stuff of legend, and Peppiatt’s biography gives a fascinating insight into Bacon’s sexual habits and social rhythms. I have no idea if it’s possible to analyze the work of an artist or scientist in any sort of rigorous way by studying their social and sexual exploits, so I’ll simply mark down a few thoughts I had while reading through some of the more personal and anecdotal passages of the biography.

Many people seem interested in making some sort of connection between Bacon’s love of gambling and his notions of “chance and accident” as they relate to painting. To me, this connection is ill-considered, and seems to distract from Bacon’s main point when he’s talking about chance and accident in the act of painting. To my mind, when Bacon speaks of chance and accident, he’s using these words to describe a very particular approach to oil painting.⇥ Oil paint is exceptionally malleable - it can take weeks for an application of conventional oil paint to completely dry. Until that point, it’s possible to easily reshape, remove, or completely rub out portions of a painted composition. The slow-drying nature of oil paint makes it an ideal medium for compositions which might need to be rethought or reworked over a long period of time. What’s interesting about Bacon’s technique is that he did not take advantage of this affordance. Instead, Bacon chose to paint on the unprimed side of the canvas, forcing the paint to dry very rapidly and resist any attempts at clean removal. This approach makes it effectively impossible to wipe out or remove unwanted strokes. Once a mark is made, it cannot be removed, only combined with subsequent strokes. An approximate analogy might be using a program like Photoshop without any “Undo” command. Peppiatt writes, “It was chance, Bacon held - the slip of the painting hand, the dribble of paint, the collision of shapes - that gave the image its necessary injection of the unforeseen” [p. 89] In his 1985 interview with Melvyn Bragg, Bacon explains the distinction between chance in gambling and chance in painting, “The accident in painting is ... you can use it, you can develop it, whereas with gambling, everytime the wheel spins there isn’t anything you can do about it”. This approach to painting is inherently risky, and Bacon was ruthless with works that did not turn out well. One of the most fascinating aspects of Peppiatt’s biography is learning of the huge number of canvases that he intentionally destroyed throughout his career. [p. 92, 407]

Before reading Peppiatt’s biography, I had no idea that Bacon had such an extreme masochistic streak. He was treated rather brutally by many of his partners, and the biography is full of accounts where Bacon is found beaten and bloodied by one of his lovers. This is not a facet of Bacon you’ll find in the interviews and documentaries from the 60’s, 70’s, and 80’s. Peppiatt notes, “It would be true to say that, at one level or another, much of what he painted is a projection of sadomasochistic practices, though, as if by some odd consensus of propriety, his pictures were almost never viewed in this light during his lifetime.” [p. 72] In his 1966 interview with David Sylvester, Bacon partially justifies his desire to paint from photographs instead of from life by saying, "If I like them... I don’t want to practice the injury that I do to them in my work before them... I would rather practice the injury in private, by which I think I can record the fact of them more clearly."[Italics are mine] I don’t know if it’s fair to interpret everything about Bacon through the lens of masochism, but this sort of statement does take on a subtlely different tone once you’ve learned of Bacon’s sexual proclivities. His choice of subject matter also lends some credence to this interpretation. For example, it might possible to explain Bacon’s early fascination with images of extreme suffering and power like the crucifixion and Velázquez's portrait of Pope Innocent X in light of his masochistic leanings.⇥ Bacon however, characteristically downplayed his choice of subject matter, claiming to have painted reinterpretations of Velázquez’s Pope simply because it gave him an excuse to use bright and beautiful colors.

The thing I find most fascinating about Bacon is his ability to speak so eloquently about the creative process and the act of painting. It’s quite rare for creative individuals to be able to converse articulately about the “how and why” of their processes and motivations using conventional language. Normally, creative people make physical (or digital) artifacts precisely because it’s difficult to articulate their feelings in a written or conversational manner. Bacon was a gregarious and prodigious drinker, and my impression is that he honed a body of incredibly clear, insightful, and seductive rhetoric over years of lively, boozy conversation about art and image making. Some of the most fun passages in Peppiatt’s biography give you a feeling for the evenings when Bacon would hold court at a restaurant or The Colony Room bar in Soho, conversing about all manner of things with all manner of people. Aside from his repertoire of funny quips and insights, I find some of his thoughts on painting to be astoundingly beautiful,

FRANCIS BACON

All page numbers referenced in this document refer to the revised and updated paperback edition of Anatomy of an Enigma printed in 2008.

N.B. that the title of the work is Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, not the Crucifixion. It’s a distinction that was important to Bacon, who was also an avowed atheist. For Bacon, the crucifixion was merely representative of the ways in which man mistreats man. As a point of comparison, his friend and contemporary Graham Sutherland would paint the crucifixion in 1946 with all the reverence of a devout catholic. For Bacon, the crucifixion was simply, "A marvellous armature on which to hang all kinds of thoughts and feelings" [p. 119]

Re: Bosch and humor, see the right panel of the Garden of Earthly Delights.

See Patricia Failing's excellent lecture, Bacon's Bodies: Trapping the Convulsive Figure

Bataille's choice of imagery makes the dreamy work of more "mainstream" surrealists (Dali, Magritte, etc) look positively whimsical.

N.B. Rubens depicts Saint Sebastian - whose flesh is literally punctured - as a solid and sturdy human form. This is the opposite of the porous, exposed, and fragile bodies of Bacon's work.

Peppiatt spends a great deal of time in Anatomy of an Enigma investigating the sexual component of Bacon's fascination with the mouth. Bacon himself acknowledges this potential connection in his 1966 interview with David Sylvester, but quickly directs the conversation towards the purely ocular appeal of the mouth. It's also interesting to imagine that Bacon's preoccupation with the mouth is somehow related to his chronic asthma - that Bacon is not painting the scream, but rather the act of labored breathing.

N.B. The striking similarity between the following quote by Soutine, and Bacon's remarks about painting flesh and the mouth. Soutine: "Once I saw the village butcher slice the neck of a bird and drain the blood out of it. I wanted to cry out, but his joyful expression caught the sound in my throat…This cry, I always feel it there. When, as a student I drew a crude portrait of my professor, I tried to rid myself of this cry, but in vain. When I painted the beef carcass it was still this cry that I wanted to liberate. I have still not succeeded."

Fascinating anecdotes about eccentric painters don't get any better than the story of Soutine's creation of the Carcass of Beef.

Of course, every painting from Lascaux to Titian "anticipates" the Post-Impressionists. Mostly, I'm trying to evoke the emphasis on the physicality of paint itself that the Post-Impressionists are famous for.

Bacon had little interest in "Illustration", and often used the term in a derogatory manner to describe dead or dull painting which did not directly, "assault the nervous system", but merely reproduced the visual appearance of some object. Peppiatt writes, "For Bacon, the test of an image which ‘worked’, to use the artist’s own term, was in part its resistance to any logical or coherent visual explanation; everything that failed this stringent test fell into the despised category of ‘illustration’. ‘After all, if you could explain it,’ he would insist with manic bonhomie, ‘why would you go to the trouble of painting it?’" [p 117] Bacon was also critical of overtly narrative visual art for the same reasons. He actively avoided including anything into his pieces that might be regarded as storytelling or narrative devices, vehemently denying any accusations that his paintings were intended to, “tell a story”.

DAVID SYLVESTER, critic

Another painter who remained resolutely figurative throughout the twentieth century was Bacon's friend and contemporary, Lucien Freud. The two were exceptionally close for a time, meeting almost every day for extended periods of their friendship.

I can't help but feel that these sentiments about abstraction may be helpful in terms of evaluating the growing body of computer-based art, especially art which is procedurally generated.

The quintessential image of Bacon's studio is one strewn with heaps (literally) of photographs and clippings. In a weird turn of events, his actual studio was transported to Dublin, where it now functions as a museum and gallery.

MICHAEL PEPPIATT, author

After learning of his son's homosexual tendencies, Bacon's father sent him to Berlin with a stern chaperone tasked with setting him straight. This trip coincided almost exactly with the height of Berlin's decadent period in the early 20th century, and the chaperone was a man in possession of enormous sexual appetites. Bacon would later recall that he was the sort of man who, ”Fucked anything that moved”.[p. 33] It doesn't take a great deal of imagination to understand how this backfired in one of the most spectacular parenting miscalculations of all time.

Bearing little resemblance to the “chance and accident” of Surrealist automatic drawing and painting where the intent is to create images through an irrational or subconscious process. Bacon’s method is a rational and focused process which leverages and exploits chance events and accidental events on the canvas to create highly ordered images. Bacon actually submitted his work to an international surrealist exhibition, but it was rejected on the grounds that it was, “Not sufficiently surreal”.

Perhaps trying to work around the, “consensus of propriety”, Sylvester goes on to ask if the visual distortions in Bacon’s portraits are not in fact a metaphorical, “caress and a blow” towards the sitter.

Bacon was obsessed with Velázquez's portrait of Pope Innocent X. He painted many canvases after the image, and considered it to be the greatest painted portrait in the history of Western art. Curiously, he claims to have never seen the work in person despite having lived in Rome for an extended period of time.